- Home

- Lloyd Kropp

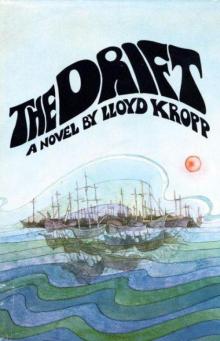

The Drift Page 3

The Drift Read online

Page 3

During his lonely years with Miriam he had imagined that love would change everything. But love never came. Miriam, he knew, had always found him cold and unspontaneous; she had never known that in his heart he was desperately romantic. At a distance he had loved many women, both real and imaginary, but he had never found a way to express love without seeming terribly foolish. Once, on a sudden whim, he had visited an ex-student, a lovely young girl named Elizabeth Greer, who had called him from time to time and had made it very clear that she had an enduring crush on him. They had talked for several hours in her apartment. Several times that week they agreed to meet, but each time she had made some excuse out of fear and uncertainty, until finally he had completely frightened her away by his insistences of love and his sudden offer one evening on the telephone to divorce his wife and marry her. It had been an altogether miserable experience, a clear indication of his inability to deal with people, his essential remoteness, his failure to communicate, his isolation from everyone and everything.

But Connecticut was still a real world where struggle and change were at least possible. It was a theatre of operations that he understood. Here on The Drift he was completely at a loss. Who in his right mind could ever cope with such a place? His muscles began to itch. How pleasant it would be to play a hard set of tennis or to climb in The Adirondacks until the sweat darkened the back of his shirt and tickled his eyes. There would have been so many pleasant things to do during the summer months if only he had stayed home—violent physical things to release the floodgates inside him and, for a time, wash away all the poisons of his bitter and lonely life.

Suddenly he noticed that the girl in the white shirt was watching him very closely. It was as if she were listening to his thoughts. “I have to go now,” she said after a moment.

She turned and climbed across the precarious catwalk that joined his ship with the next, and her departure gave him a sudden, foolish sense of loss.

“Wait! I’m afraid I—that is, I was wondering if there was someone who could show me around.”

“Oh, I forgot,” she said, calling back to him. “Tabor is waiting for you on The Cliff. That’s up on Northside. He’s going to take you all around The Drift this morning. I’ll see you at dinner.”

He was about to ask for more specific directions, but saw that she was already three boats away, disappearing now amid the forest of spars and masts and torn sails.

Slowly he made his way upward toward what he guessed was The Cliff. At first he noticed clear places between the ships where he could see the greenish swamps below, but as he neared the top, the high hulls of boats rising over each other left the narrow riverways in deep shadow. He had the distinct impression that he was on an island, and that the sea was some distance away.

Tabor was waiting for him on the deck of an old Howker, a round tub of a ship with its two bare masts pointing into the sky. He wore the same hat, a kind of mate’s cap with a black visor, and a gray turtleneck sweater. When he saw Peter he smiled and waved.

“Hello,” he shouted. “I’ve been waiting for you.”

“Good morning,” said Peter. “How do I get over there?”

“You jump.”

“Isn’t that a little dangerous?” He surveyed the five-foot gap between the boat he stood on and Tabor’s boat.

“Only if you don’t jump far enough. Otherwise it’s perfectly safe.”

Peter smiled. So the captain had a sense of humor. Well, that was something. He walked to the far edge of the boat, gave himself a running start, and cleared the edge of The Howker with nearly a foot to spare.

“That took courage,” said Tabor. “We need courageous men on The Drift.”

“An ounce or two of physical courage is one thing,” said Peter. “The courage to live the rest of my life here is another.”

Tabor looked at him very closely, still smiling. “You need courage for that only at the beginning,” he said. “Later on it takes no courage at all.

“I don’t understand.”

“I think you will after a time. But this morning I thought I’d show you around The Drift. By the way, have you had breakfast?”

“Yes. A girl came into my room this morning and brought me something. Who is she?”

“A young girl? That must have been Pao. She’s one of our clan. Lovely, isn’t she? But don’t be fooled by all that enchanting long hair and those black eyes. Pao is very quick, and very wise in some ways, and she has many talents. The first thing I learned about her is that she has a mind of her own.”

“Really?” He was curious about Pao, but he hesitated to ask pointed questions. It would be better, he thought, to wait until he knew Tabor a little better and until he understood more about his own status among the people who lived here.

Together they walked to the north rail of the old Howker and looked out into The Sargasso Sea. A large island of gulfweed turned in a slow circle a hundred feet or so beyond the edge of The Cliff.

“Everything here seems so improbable,” said Peter after a moment. “Like something out of a dream.”

“That’s the way everyone feels when they first come here,” said Tabor. “But actually The Drift was inevitable. Perhaps it’s always been here.”

“But what makes it all happen? I can’t believe that the old salt stories about The Sargasso Sea are really true. It’s too fantastic.”

Tabor smiled. “In many of the old stories there’s a giant whirlpool that draws everything together, but actually The Sargasso Sea is rather shallow and rather poorly defined. Currents are never quite the same from season to season, and the inward motion is very generalized and inconsistent. The Gulf Stream and The West Wind Drift move north and east above us, and The Canary Current and The North Equatorial Current move south and west below us, and that does make for a relatively calm circle that rises a little in the center, a sort of lens-shaped sea of warm water that floats on top of the deep layers of The Atlantic. And so the currents drift inward and deposit things—driftwood, weeds, and the like. But that’s about all it amounts to. The small islands of weeds and the animal life that lives on them are fascinating of course, but beyond that—”

Peter waved his hand impatiently. “I understand about The Sargasso Sea,” he said. “But what about The Drift? I would think that everything would simply move around in an aimless way over a large area. Why has all this collected in one place?”

“If you drop petals in a large washbasin and then move your hand around the edge, all the petals will eventually gravitate toward each other as the current moves them in the same direction,” said Tabor. “With an inward-moving current they collect near the center. I think that’s part of the answer. And of course there may be other factors we know nothing about. For example, I sometimes suspect that there’s a local eddy, a vortex of some kind that no one has ever discovered. I don’t know what would cause such a thing. Perhaps a high mountain ridge on the ocean floor that affects the deep currents.”

“That’s a little hard to believe,” said Peter.

“Many things here are hard to believe,” said Tabor. “All the stories about The Sargasso Sea have an aura of the fantastic. They all suggest that strange powers operate here. The Carthaginians and the Greeks told stories about a sea of spiked grass near the western edge of the world that was inhabited by monsters. Later there was a tale about how The Lost City of Atlantis lies at the bottom of The Sargasso Sea. Some of the elders still talk about Atlantis. They say that people still live down under the sea, that they exert some sort of influence over us and that the vortex is their doing. But of course that’s only superstition. All we really know is that derelicts and weeds and other lost things are moved by the currents and eventually find their way here.”

“I see,” said Peter. But he was disturbed by the expansive, imprecise nature of Tabor’s explanation. Petals in a washbasin. Unexplained currents. Lost cities. Tabor’s words had increased rather than diminished the feeling that nothing here was real or even plausibl

e.

“At any rate,” said Tabor, “The Drift is a fact. I’ve lived here for over twenty years now.”

Twenty years. That in itself was implausible, unacceptable. His mind rebelled against the possibility of living twenty years in a graveyard of antique ships. He looked up and saw that Tabor was still smiling a little, as if something were vaguely amusing.

“But why is it that no one knows about you? Why haven’t you been rescued in all these years?”

Tabor hoisted himself up on the wooden railing of the ship, which creaked under his weight, and lit his pipe. “There are several reasons for that,” he said. “First of all, we take up very little room in the middle of The Atlantic Ocean. Except for some outlying wrecks, The Drift forms a sort of ellipse that’s less than a mile long and only about six or seven hundred yards wide at its midpoint. It seems enormous from our vantage point, but it’s hardly the sort of thing that anyone is likely to discover in all these thousands and thousands of miles of water. The nearest air and shipping lines are hundreds of miles away. Perhaps it’s never occurred to you, but there are still vast areas of the ocean’s surface that no one has ever seen, simply because no one has had any reason or occasion to go there.

“Of course there have been a number of scientific expeditions to this part of The Atlantic—in fact I have some recent books on oceanography from a small expedition ship that drifted in about two years ago—but even so we have to remember that The Sargasso Sea is in itself about two thousand miles long. The Drift is still only a pinprick on the map.”

“But surely in all these years someone must have discovered this place!” said Peter. “It just isn’t reasonable to think that no one has rescued you because you’re off the trading lanes. Too much time has passed. People have been exploring and crossing The Atlantic for hundreds of years.”

Tabor sucked on the end of his pipe and let the smoke drift out into the blue air, watching until it dissolved into nothing. “It’s true that people sometimes stumble across us,” he said. “Once in a great while we see a plane flying overhead. But I don’t imagine they really see what’s here. One sees what one is prepared to see, I suppose. And no one is prepared to see a myth. Perhaps from a distance we look like an island, especially with all the vegetation floating around us. Ships, that is, ships under their own power, are much less frequent. The last time was about three years ago. Three American fishing vessels sailed by, sloops I think. Something like the schooner where you’ve been quartered. They never got close enough for us to signal or call out, so we never knew quite what they saw or what they thought about what they saw. We waited for months, but no one ever came back. If they did see us clearly I suppose they finally decided we were some sort of hallucination, or perhaps a figment of the devil’s imagination. Or perhaps they did tell people about us and were simply laughed at. No one believes the tales of a sailor. Not even other sailors.”

Peter smiled tolerantly. All of Tabor’s explanations seemed to be diversions, clever words that only skirted with the truth. It was annoying. The man seemed to be playing with him. “I still don’t understand,” he said after a moment. “So far you’ve attributed everything to chance and human error. It seems impossible that with hundreds of thousands of people crossing the oceans every year in ships and planes, no one has found you. Surely in the last hundred years—”

Tabor nodded in agreement. “You’re right, of course,” he said. “There are other factors. But I was hoping to avoid the more scientific explanation.”

“Why?”

“Because it makes everything seem so final. I think it’s better for a newcomer on The Drift to feel for a while that life here is some kind of elaborate hoax and that he will be back on firm ground soon enough.”

“Never mind that. What’s the real reason you haven’t been rescued in all this time?”

Tabor looked down over the edge of the boat into the water, and in an absent way he began to scratch his beard. “The scientific reasons,” he corrected. “The other reasons are real enough too.”

“The scientific reasons, then,” said Peter.

“Well, first of all, there’s something very strange about temperature conditions just outside The Drift. The water seems to be unusually cool and the air unusually warm by comparison. Perhaps there is a deep current that surfaces out there somewhere; perhaps there is an eddy of warm air. I don’t pretend to know what might cause all this, but that’s not important. What’s important is that it constitutes a temperature inversion, a reversal of the normal continuum of warm to cool as one moves from sea level up to the stratosphere.”

“I don’t understand what that has to do with the fact that no one has ever discovered this place,” said Peter.

“Temperature inversions affect visibility,” said Tabor. “First of all, there is a continual condensation of mist where the warm air meets the cool water, and so the air is hazy much of the time. This in itself makes The Drift difficult to see from any position. But there are other problems as far as visibility is concerned. Temperature inversions also mean abnormal refractions—queer bending of light rays that trick the eye in a number of ways. This is especially true, for example, in antarctic regions where there is often a marked difference between water and air temperature. Sometimes things loom above the water, flatten out, sink into invisibility; sometimes there is a blurring or streaking that destroys the outline of what you’re looking at.”

Peter crossed his arms and tried to look unconvinced. “I never heard of that,” he said flatly. Then he looked up and saw that Tabor was smiling at him again. Suddenly he had an image of himself as a petulant child who would not believe anything that anyone told him. “But of course I’m not a scientist,” he added.

“Neither am I,” said Tabor. “But I know the ocean, and the ocean is full of optical tricks. I remember once back in nineteen-thirty I was sailing on the Mauritania. I was only a boy then, but I remember it very clearly. My father and I were on the deck one morning and suddenly we noticed that a ship was sinking about a half mile off. It disappeared completely under the water, and I remember some woman cried, ‘My God, she’s gone,’ or something like that. But then the boat reappeared again a few minutes later. Then it seemed to bulge in an odd way and break in two pieces. Everyone was mystified, but my father smiled and said that the ocean air was full of poltergeists and that he had learned that well enough sailing clipper ships out of London Harbor in the old days.”

He laughed. “I don’t think he ever told me a sea story I didn’t believe after that,” he said.

“Interesting,” said Peter.

“There are some even stranger things that are attributed to temperature inversions,” said Tabor. “Have you ever heard of Deception Island?”

“No.”

“It’s one of The South Shetlands. Apparently it changes shape, position, and even becomes invisible a good bit of the time because of temperature inversions that seem to be a consistent part of the climate in that part of the world. A friend of mine was a member of a scientific expedition to The Shetlands about thirty years ago, just before the war. He said they searched for a whole day, moving in circles at the map coordinates where the island was supposed to be. They had no luck at all until all of a sudden there was a shimmering in the air and two pinnacles of stone appeared before them out of nowhere, guarding the entrance to the bay of the island. It was like a dream.”

“It sounds more like a miracle,” said Peter.

“Perhaps so. But then, the ocean is full of miracles,” said Tabor.

Peter looked out beyond The Drift to where wisps and feathers of mist seemed to be rising and rolling above the surface of the water. He could not see the horizon. “It must clear up sometime,” he said dismally.

“Sometimes the air seems quite clear,” said Tabor. “But air is always an uncertain medium, especially above water. It’s filled with inconsistencies of temperature and density that are like little mirrors and lenses, some only an inch, others nearly a fo

ot long, always changing, shifting. Over any reasonable distance it’s very difficult to see clearly if there are abnormal atmospheric conditions. When I was a sailor it was not uncommon for ships to pass within a space of two hundred yards without ever seeing each other.”

Peter smiled. He remembered Tabor’s little joke about the leap that was not at all dangerous if only one jumped far enough. It was like his whole specious explanation of this impossible place: the inductive leap was reasonable enough if one was capable of making it, and that seemed to him a matter of faith. He thought about the illusion of the sinking ship and the disappearing island, and he looked around him at the huge wasteland of ships floating in a caged sea. Nothing seemed to make sense.

He shook his head. “Well, as you say, The Drift is a fact. I suppose I’m bound to accept that. But I still don’t understand about all the ships. Most of them are so ancient. Why haven’t they just rotted away in all this time?”

“Everything that comes here decomposes eventually,” said Tabor. “But it does take longer than it would in harbor or in the open sea. I don’t know why exactly. There are so many things about The Drift in particular and The Sargasso Sea in general that I may never understand. The salinity of The Sargasso Sea is higher than in any other ocean. Recently someone discovered that between the five-and eight-hundred-meter mark there’s an unusually high percentage of strontium. And then perhaps you’ve noticed that the water here has a subtly different smell. I don’t know what all these things mean. Perhaps they’re part of the reason why the boats disintegrate so slowly. Perhaps not. We do some repairing and caulking and painting, but of course our resources are very limited, so that could only be a part of the answer.”

“How about the number of old ships as compared to the number of new ones?” said Peter. “Or is that another mystery of the sea that no one can explain?”

“That’s no mystery at all,” said Tabor. “Ocean liners and warships are generally larger and much stronger than wooden ships. They don’t flounder as easily in storms and they don’t get blown hundreds of miles off course. And most of them have long-range radios and radar and sometimes even their own foundries for damage repair. Then too, the loss of a large modern ship is a national event. Within hours there are planes and ships answering distress signals. And so there are far fewer modern derelicts. Most of the ships on The Drift are between sixty and three hundred years old. The only newer ones are small fishing boats and cabin cruisers. This means of course that The Drift will slowly get smaller and perhaps even disappear unless the world plunges into a dark age and people forget their steel technology and atomic power plants, and begin to build wooden ships again.”

The Drift

The Drift