- Home

- Lloyd Kropp

The Drift Page 21

The Drift Read online

Page 21

“I’m sorry,” said Peter.”

Again the old man began to mumble, and his eyes lost their focus. He seemed to have forgotten that Peter was still there, hesitating at the doorway with his can of gasoline.

“Even so, there’s something left in the music,” he was saying. “Something that’s not a part of them. That’s why they’re afraid of me. I still remember the old world, even after all these years. And the music remembers too. Bach. Vivaldi. Scriabin. Sibelius. The music even remembers some things that I’ve forgotten. I have to listen sometimes with my other ear, the one inside my head.”

“I have to go now,” said Peter. “Thanks for the gasoline. I needcd the gasoline very much.”

The old man suddenly took notice of him again. He stood up at the piano. His face was lost in shadows. “I make you uncomfortable, don’t I?”

“No. Not at all. It’s just that I have to go now. Thanks for the gasoline.”

“It’s all right. I make everyone uncomfortable. I’m an ugly, ancient old man. Should have died years ago. Be gone soon and then I’ll be no bother to anyone.”

Peter looked at him helplessly. There was nothing to say.

“You’re doing the right thing,” said The Hatchmaker. “I can see what you are in your eyes. They’d hate you too if you stayed too long. You’d be an Outlander, like all the other good men.”

“Do you know The Outlanders?”

“They come here to trade with me sometimes. Think of me as their leader. The Revered One. Yes, I know The Outlanders very well. They spoke of you once. Old Grayfish told me you were a man of great courage. That’s what I see now in your eyes. That’s why they’d hate you on The Drift if you stayed too long. They hate anyone who lives as a man should live.”

“But The Outlanders attacked me,” said Peter.

“Yes. They test you by trying to kill you. It’s their way, ugly monsters that they are. They knew if you lived to stay here you’d soon be one of them. Brighteye—he’s the one you dumped into the water—he rather likes you. He knows about motors and he knows you’re trying to get off The Drift.”

The old man began to chuckle. “You scared the others,” he said. “Most of them never heard motors. They told Grayfish about The Devil that roared in the boat. He laughed for nearly an hour. If he’d been along you wouldn’t have gotten off so easy.”

“I really have to go now,” said Peter.

“Of course you do,” said The Hatchmaker.

“Thanks for the gasoline.”

“You said that before,” said The Hatchmaker.

The old man was still standing at the piano. He did not look directly at Peter. His head was tilted away toward the shadows in the far corner of the room where Peter had found the gasoline. His white fingers rested on the black frame above the keyboard. He was like a blind man feeling his way, his head turned away a little from the direction of his movement, his hands reassured by the touch of familiar objects.

“I’d like to go with you,” he said, “but I’m too old now. I’d never live through the journey and I don’t want to die on the open sea. Better to stay here. I’ll die here at the piano where I’ve lived for all these years.”

“Good-bye,” said Peter.

“Good-bye,” said the old man. “I’d hoped you might come back again. You see, it’s very lonely here and I’ve enjoyed our little talk. The Outlanders don’t talk much. But you won’t be back, will you?”

Peter hesitated before answering. “No,” he said. “I won’t be back.”

“Well good-bye then. And have a good journey.”

The old man raised his hand to wave, and from across the room Peter saw the shadow of his hand cast by the flickering lamplight on the wall behind the piano. He closed the door and made his way back upstairs.

“Good-bye,” wailed the old man from the dark room, his voice rising like a ghost through the wooden compartments and passageways of the ship.

When Peter reached the deck he gasped for air. It was as if he had not breathed for hours. Inside, he was sick with pity. He looked up at the stars and felt the cool, windless night against his face. Then he looked down at all the broken ships around him, and his pity opened like a river to engulf everything on The Drift.

Then, slowly, his pity turned to loathing. Had he been mad? Would he have given his whole life to live here in this hopeless ruin? His whole life given for a song? He thought of the old man and the ruined fingers that had played a ruined melody for sixty years. He thought of Raven’s bitterness and his council of rats. He thought of Tabor’s passive spirit and of the old ones who sat in their circles for days without stirring. He thought of the shark to whom he had nearly given his life. It was as if he had walked in his sleep to the edge of some fearful cliff and had tried, in the logic of dreams, to give his life for the joy of plummeting through the windy air, for the joy of being a meteor, a heavenly body whose destiny it is to burn fiercely and then break apart, to dissipate and become one with the air and the earth. It seemed now that he was standing, fully awake, at the edge of that cliff and looking down at the broken, misshapen things below him.

Yes, he thought, it was all madness. Perhaps even his love for Pao was a perversion of normal love, a longing for youth and for the young manhood that he had never fulfilled, mixed with a regressive, incestual passion for the daughter he had never had, that phantom child through whom, in the furthest reaches of his unconscious, his youth had been twice lost: once by time and again in his childless middle age.

As he made his way down toward The Southern Edge, it occurred to him that there would be no way to explain all this and no hope of anyone coming with him even if there were enough provisions and enough room in his aluminum dinghy to hold them. He would never be able to face Tabor and Pao in the morning, and a confrontation with Raven would be even more difficult. There was only one thing to do. He would leave now in the darkness before anyone found out. Raven had supplied his boat with everything he needed. In two hours he could be far out into The Sargasso Sea.

Above The Drift the moon was rising. For a moment he turned and looked behind him. Everywhere in the old ships the fish-oil lamps were winking out one by one.

Nineteen

WHITE FLOWERS IN A BOWL

After he had stowed the gasoline in his dinghy, he walked back to the cabin of his ship to pick up his compass and the white shirt that Pao had made for him and an armful of other supplies. He hesitated for a moment at the door and then quietly opened it. The room was empty. He entered, closed the door carefully behind him, and lit his lamp.

Pao’s note lay undisturbed where he had left it. On his bed there was a depression, and across his pillow lay a long strand of black hair. He wondered how long Pao had lain there, her long hair falling across the pillow. Perhaps she had left only a moment before he came. How, he wondered, would he ever have had the power to leave if he had found her sleeping in his room? Why had he risked everything by returning here one last time? Certainly The Hatchmaker would have given him a compass. He knew the answer without really forming the words in his mind: part of him would always long for The Drift—the corner of his mind that for a few days had persuaded him to forget his whole life for its sake. He stared at the water hyacinths that floated in the brass bowl on his dresser. They drifted in a slow circle around the edge, as if blown by a tiny, soundless wind. White flowers in a bowl. Drifting. And in the moment before he extinguished the lamp and the room went dark, he could feel Pao’s touch upon them. Her white fingers were the wind that blew the slow, delicate petals in a circle.

An hour later he lowered the dinghy into the water. He made a quick check of everything in the boat: motor, twenty-five gallons of gasoline, paddle, eight jugs of water, dried fish and seabread, hook and line, net, compass, two blankets, rubber poncho, rope, two shirts, hat, sweater. Then he pushed free of the old bilander and began to paddle through the weeds toward the open sea. He was alone now. With that one step he had left Pao and Tabor and The Mary S

trattford behind.

Then it occurred to him that he had never seen The Drift from the water. He wanted now to paddle around it in silence and watch it unfold like a revolving stage. It would be a way of saying good-bye.

Slowly he paddled along the edge of The Outland. The brilliant moonlight in the clear sky illuminated everything. It was like an enormous junkyard, an island of the dead. But after he passed Driftsend it assumed its familiar romantic character. The ships loomed above the light mist that had gathered on the water like broken cathedrals after an earthquake, tilting at insane angles against the moonlit sky.

He paddled westward along The Northside Cliff. Once he tried to raise his sail, but there was no wind anywhere. For a while he stopped paddling. After drifting a few minutes he started the engine.

Suddenly a yellow light appeared in one of the old schooners. And then another. He thought of the time he had started the motor to scare the Outlanders. Then people began to appear at the sloping edge of The Cliff. He heard their wavering voices calling out to him across the water. Tabor waved at him and shouted something. One figure appeared very near The Mary Strattford. It was a young girl, but in the moonlight he was not sure if it was Pao or one of the girls from The Madrid. She waved to him just once. She did not move or call out to him. He watched her as she followed the course of his boat, as she followed the widening gulf of water between him and The Drift. And then the shadows of the night closed about her and he could see nothing but the yellow lamps and the outlines of the boats. Soon the individual shapes of boats blurred together into a long curved line near the horizon. Then the moon moved behind a cloud and The Drift disappeared completely. The mist was growing heavy now. He turned away and set his course south by southeast. Perhaps in two or three hours he would be out of the windless center of The Sargasso Sea. Then he would raise his sail and let the wind carry him into the trade lanes.

An hour later the peaceful life on The Drift seemed far behind him. Ahead was the open sea, a sea of uncertainty and perhaps death. He felt an unreasonable longing for all the things he had given up so easily. He remembered The Seafields in the morning sunlight, the netted pool, the hours alone in the dark with Pao, the book he and Tabor had planned to write. Now, if he lived through the coming ordeal, he would return to his old life.

His memory of that old life was slow and disconnected. A few odd recollections, like pieces of driftwood on an empty beach. The stony face of his department chairman. His house in Connecticut. The meetings of the historical society he had attended last year in Philadelphia. Miriam.

In the old world there would be dozens of things to take care of if he ever did get back, and he would face everything alone. Back there he had always been alone. How different things had been with Pao and Tabor on The Drift. Suddenly it did not seem to matter that for The Hatchmaker, for Raven, and for The Outlanders, The Drift was a Lotus Land of illusions, a failure of the will, a prison where nothing real was possible. His other life had been no less a prison, no less filled with false hope, ghosts, delusions. And how much less beautiful it was. It would have been better, he thought, to give up the absurdity of human aspirations in the civilized world of torpedoes and machine guns, where sane men told lies and madmen told truths, where men without vision nodded to slogans and men with vision were crucified, or worse, ignored, where order was a virtue even when when it came out of fear, ignorance, or inertia, and disorder was a heresy, even when inspired by genius.

On The Drift there was love, peace, a chance to live simply and with dignity, a chance to dream one’s life away in contemplation. All his life, it seemed, he had been looking for a world to live in. Not a world of bored students and classrooms, not Miriam’s world of cocktail parties and country clubs, not his own empty childhood in the streets of Paterson, New Jersey, a childhood lorded over by his pious mother and his stern father, both victims of their Christian guilt and their hatred of the world—not these, but another. A place hidden out of time’s way. Something beyond the turn of things, where he could set free the real energy of his mind, whatever that might be. A place where he might let go of all his useless fears and petty ambitions. A place where he could leave behind the curious silence that had followed him through the years.

He rested his hand on the tiller of the outboard motor. It would be easy to turn back. He had come only a little way. But the night was all around him now and a fog was settling on the water. He could not even see the dial of his compass.

He pushed the tiller to the left and the boat began to veer in a wide arc to the right. But how far, he wondered, should he turn? How would he know in this darkness whether he was going back in the right direction? His hand froze on the tiller, and the boat made wide circles in the water. He could not make up his mind. He closed his eyes and wished suddenly that the darkness would swallow him up.

When he awoke he was drifting somewhere in The Sargasso Sea. The sun was rising and the luminous clouds in the east hovered near the horizon. He ate some seabread, drank some water, and raised his sail. For hours he thought of nothing. He listened to the sound of the water and the sound of the wind in his sail. He was moving southeast.

By the fourth day his food and gasoline were gone. On the sixth day he caught a bonito and ate it raw. During the long morning and afternoon hours he thought about Pao and The Drift almost constantly, but by the end of the first week and a half he was numb with hunger and thought of nothing but food. On the tenth day he ran out of water. On the twelfth day he was saved when it rained for three hours. The rain brought him out of his stupor and he collected enough in his eight jugs to last another five days. On the fourteenth day he ran into a school of fish and caught nearly a dozen in his net.

The wind was steady. By day it carried him through the yellow arc of the sun’s journey; by night, toward The Pleiades, hovering near the eastern rim of the sky.

On the sixteenth day he slept in the shadow of his sail until noon. He dreamed that his boat had drifted north, back to The Sargasso Sea, and that Pao was waiting for him. Then, with the high sun in his eyes, he awoke. He had a fleeting memory of Pao running away, fading, resolving into something small, distant. White flowers in a bowl of water.

He blinked in the bright glare of the sun and then stared at the horizon. A line of black smoke rose in the west. In ten minutes the smoke had lifted over the outline of a large merchant ship. A half hour later three men in a motor launch towed his dinghy toward the enormous gray hull.

After he had boarded the ship he shook hands with the captain, a portly smiling Dutchman, was treated to a large steak and a glass of orange juice, and then slept for two days.

Twenty

THE DREAM

The next week he returned to Harrington University. It was like returning to a life he had lived in a previous incarnation. The long carpets of grass, the gravel parking lots, the concrete and glass dormitories, the incredible noise of shouting students and automobiles all seemed to be from a different century, a different age. Suddenly he was a thousand years old.

His return caused, as he had imagined it would, a good deal of confusion and embarrassment. Everyone was terribly surprised. The response of his colleagues in the History Department and of his wife’s friends somehow confirmed his own view of himself. He was a stranger here in this polished world of libraries and classrooms.

Dr. Ratcliffe was friendly, as always, but there was the distinct impression that his resurrection from the dead was an inconvenience, a breach of etiquette.

“It’s very good to have you back, Peter,” he had said that first afternoon in his office. Dr. Ratcliffe had not changed, but Peter saw him as he had never seen him before. The pursed lips, the gray face, and the cautious formal nod were all so characteristic of him, but now they seemed strange, like the gestures of a mannikin.

“Of course you realize that we’ll have to put you on leave of absence until next semester since we’ve already hired Mr. Reston to teach your courses,” he was saying. “But please don�

�t hesitate to call on us in the meantime. Anything we can do to help—”

Peter was edging toward the door. “Yes, sir. Thank you very much.”

“You must have had quite an adventure, lost all those days on the water.”

“Yes, sir. It was quite an adventure.” Peter stood in the doorway. He glanced down the long empty hall.

“We must talk about it sometime,” said Dr. Ratcliffe. For a brief moment he made a pinched smile that sharpened all the lines in his face. His smile, as always, was sudden and mirthless, a convulsive movement of his cheeks and lips that spoke only of emptiness and old age.

Peter smiled and nodded and closed the door behind him.

That evening there was a party at Miriam’s house. The pale, elegantly furnished rooms were filled with dozens of people whose names he at first could not remember. After a few minutes he stepped out onto the stone patio to hear the sounds of the cool October evening. The stars above him were infinite and bright. He remembered the old astral globe in the navigation room of The Hatchmaker’s clipper ship. He remembered the arrows of Sagittarius pointing north, between Arcturus and Andromeda, into the empty sinking spaces of that curved eternity. He had meant to give it to Raven as a sort of gesture of friendship. Something he could keep in his own room with all his maps and magazines.

Gradually others drifted out onto the patio. There was an aging tennis player named Basil Queen who had no hair and who read Kipling, and his very slender wife who drank too much and who ate nothing but soft-boiled eggs, except on weekends. There was Tony Berendtson, a young man with soft blond hair who had once worked in his father’s oil refineries in New Jersey for six months, who lived with his mother and his astrologic charts in Provincetown and who had seen Swan Lake seven times. There was Harry Ranton, Miriam’s new lover, who owned his own real estate business and who drank everything straight. There was Miriam herself, the gay divorcee in her yellow silk dress, who loved men, hated women, despised dogs, cats, and scholars. There was Miriam’s younger sister, Beverly, a plain, flat-nosed girl of nineteen with a figure like a surfboard who always talked about The World of Feeling and who would probably never marry. And there was Mary Rhys Beacher, a well-known Boston psychiatrist who at that moment was telling her many disciples, who sat around her like tame geese, about The Renaissance Image of The Dance of Life. Soon Peter was driven back into the living room.

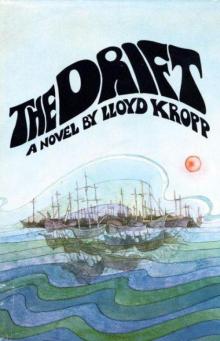

The Drift

The Drift